Topic 2: Childbirth

“When do I go to hospital?”

Ask about the best time to go to hospital at one of the antenatal visits. If this is your first baby and you are well prepared and confident, you will probably be advised to go to hospital when contractions are at regular five-minute intervals and are moderately strong. On the other hand, if you live some distance from the hospital, it might be best to go into hospital as soon as labour starts.

If you feel anxious, no matter how early in labour you are, head for the hospital. Do not worry if you arrive early—the main thing is your peace of mind.

Ring the hospital before you leave and speak to one of the midwives in the delivery suite to let them know you are on your way.

If you are travelling to hospital by car and feel as if the baby is about to be born, go to the nearest hospital, even if it is not the one you booked into.

“When does labour begin?”

Labour can start some days (or one to two weeks) before the due date, or up to two weeks after it. It can start in one of several ways—with contractions, a “show” or breaking of the waters. These can happen in any order.

These may be mild at first. Your back may ache or you may notice the sort of aching, heavy feeling you sometimes get with a period. Gradually, these contractions become more regular, closer together, longer and more painful. You will know they are the real thing when they become stronger and more frequent. You may also feel sick, vomit or have diarrhoea.

During pregnancy, the cervix (neck of the uterus) is partly sealed with a plug of mucus. Before or during labour, this plug comes loose and passes out of the vagina. If this happens before labour, it may appear in the toilet or on your underwear as a small amount of pinkish mucus—it is a sign your cervix is starting to stretch. However, it may be several hours or perhaps a day before contractions start or your waters break.

The membrane bag that holds the baby and the fluid it floats in (the amniotic sac) may burst at the beginning of labour or when labour is underway. Fluid may leak or gush from the vagina.

As soon as your waters break, contact the hospital or birth centre. Prompt medical attention is required as a safeguard against infection. The hospital or birth centre will ask you to go in even if there is no sign of a “show” or contractions.

Once labour begins, you may be told not to eat or drink anything. This is to prevent you from feeling sick later on in labour. It is also a precaution in case a Caesarean is necessary and you need a general anaesthetic. However, you can keep your mouth moist by sucking ice or barley sugar or having sips of water.

If labour starts during the day, continue your normal routine at home until it is time to go to hospital. It is best if you can stay as mobile and upright as possible. If it starts at night, conserve your energy by resting or sleeping.

“What happens when I go into labour?”

When your baby is ready to be born, it will usually be curled up with its head down, arms tucked in and knees bent. (Birth is usually head first—this is thought to make it easier for the baby to fit through the bones of your pelvis.)

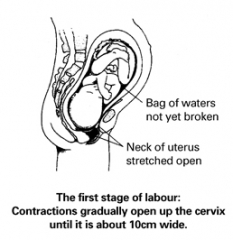

There are three stages in labour. The first stage starts with regular contractions and cervical dilation and lasts until the cervix has opened up fully. The second stage is when the baby is pushed down the vagina and is born. The third stage is when the placenta comes away from the uterus and is pushed out of the vagina.

This is the longest part of labour. Although it is anyone’s guess how long your labour will last, the average length of the first stage of labour is between 10 and 14 hours for a first baby and about eight hours for subsequent babies.

During this time, contractions gradually open up the cervix until it is about 10cm wide (this means it is fully dilated). It may not seem much, but it is wide enough for a baby to come through.

What do contractions feel like? First, the muscles of the uterus tighten up and the pressure slowly builds up to a mild, moderate or strong level of pain (depending on how far labour has gone). Then this feeling of pressure and pain reaches a “plateau”—in other words, it stays briefly at that same level and gradually fades away.

These contractions gradually intensify and come closer together until each one is about a minute long and coming at a rate of one contraction every two to three minutes. There will be a break of one to two minutes between contractions at their strongest.

During the first stage, a healthcare professional may do an internal examination regularly to see how far the cervix has opened. The baby’s heartbeat will be monitored frequently to see how well it is coping with labour. This may be done with a stethoscope or with an instrument held against your abdomen. Sometimes, electronic monitors are used.

There is a transition period or changeover between the first and second stages. It usually lasts five to 45 minutes, and you may feel shaky and nauseous. You may vomit (which will make you feel better), feel irritable, anxious and as if you cannot cope one minute longer. Not all women experience these things, but if you do, do not worry – it will not last long, and it signals progress towards birth.

This is much shorter (around 45 minutes to two hours for a first baby; between 15 and 45 minutes for subsequent babies). An urge to push will indicate second stage. You can then start to push with the contractions.

Remember, you need only stay in a squat or kneeling position for the duration of each contraction, then you can lie down or lean forward onto a bean bag to rest and wait for the next contraction. You will probably need your partner or support person to physically assist you in changing positions.

As each contraction starts and your body signals you to push, you will notice that you hold your breath (for no more than six to seven seconds), your abdomen will tense and your uterus will push your baby down the vagina. Try to keep the muscles of your perineum (the area between the vagina and anus) relaxed as you push.

Concentrate on keeping your jaw relaxed, as well as the vagina and pelvic floor. You may find you are making a noise or groaning. This is normal.

With each contraction, your body may signal three or four pushes. If it does not, you need to change your position and be more upright. You may feel as if you are going to open your bowels at this stage—it is caused by the pressure on the back passage as the baby moves down the vagina.

When the baby’s head starts to press against the entrance to the vagina and it opens, you will feel a burning sensation as the skin stretches. The doctor or healthcare professional will try to make sure the head emerges slowly by asking you to pant—this helps to prevent the skin of the perineum tearing. You may like to use a mirror to watch the baby’s head appearing through the vagina.

Once the head is through, most of the hard work is over and the baby is usually born quite quickly. After birth, most midwives put the baby onto your abdomen with the cord still attached. Your partner may be given the choice of cutting the cord.

After the baby is born, contractions will push out the placenta. You will be given an injection just as the baby is being born to help the uterus contract and to help the placenta separate safely from the uterus. This stage is usually over in about 15 minutes, after the baby has been born.

“What is a Caesarean Section?”

A Caesarean section (C-Section) is when the baby is delivered by cutting through the abdomen into the uterus. It is usually done with a horizontal cut just below the bikini line—nevertheless, later on you will still be able to wear your bikini with pleasure!

Caesareans are done for a lot of reasons; sometimes because your pelvis is too small to let the baby through or because either you or your baby is at risk and delivery needs to be quick.

Usually, it is done with an epidural anaesthetic, sometimes with a general anaesthetic.

After a Caesarean, your baby may need extra care. You will feel uncomfortable for a few days (it hurts to laugh and it is hard to stand up straight) and you may need to be in the hospital a little longer.

Do not think that you have failed in any way since 10% to 12% of deliveries need a caesarean section to ensure the birth of a normal and healthy child. As a caesarean mother, you will feel very tired after the anaesthetic has worn off. You may have a drip in your arm and a catheter (small tube) in your urethra to help keep your bladder empty.